There is considerable interest in wireless networks equipped with intelligent reflecting surfaces (IRSs), aka reconfigurable intelligent surfaces or smart reflecting surfaces. While everyone agrees that IRSs can enhance the signal over a desired link, there are conflicting views about whether IRSs matched to a certain receiver causes interference at other receivers. The purpose of this blog is to clarify this point.

To this end, we focus on a downlink cellular setting where BSs form a stationary point process Φ and a user and a passive IRS with N elements are placed in each (Voronoi) cell. The exact distribution is irrelevant for our purposes. The desired signal at each user consists of the direct signal from its BS plus the intelligently reflected signal at its IRS. The SIR of a user at the origin served by the BS at x0 can be expressed as

where ℓ(x0) is the path loss from the serving BS and

Here the random variables g0 and gi capture the (amplitude) fading over the direct link and reflected (indirect) link respectively, and the triangle parameter Δ captures the distances in the BS-IRS-user triangle. For details, please see this paper. The pertinent question is what constitutes the interference I. If all BSs are active, their interference is

But how about the IRSs? This is where it becomes contentious. Some argue that the IRSs emit signals and thus cause extra interference that is not captured in this sum over the BSs only. This would mean that we need to add a sum over the IRSs of the form

where Ψ is the point process of IRSs and pz is the power emitted by the IRS located at z. To decide whether Q is real or fake, let us have a look at the underlying network model. With fading modeled as Rayleigh, it is understood that the propagation of all signals is subject to rich scattering, i.e., there is multi-path propagation. For the case without IRSs, the propagation of interfering signals is illustrated here:

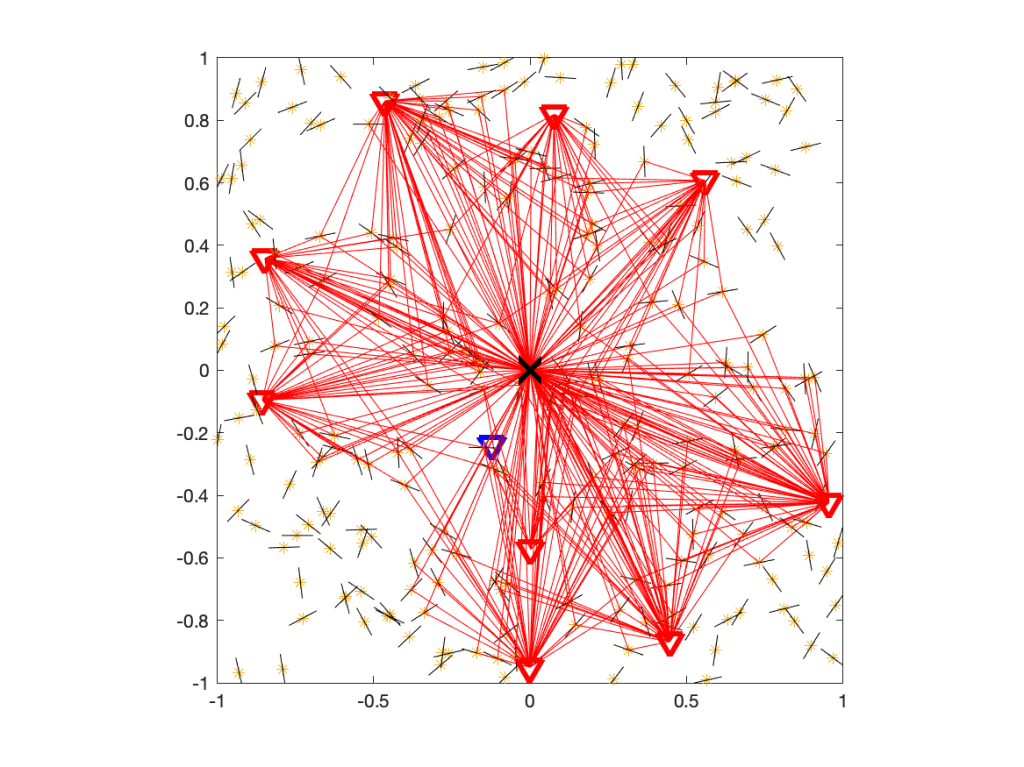

Figure 1 shows the user at the origin, its serving BS (blue triangle), and the interfering BSs (red triangles). The small black lines indicate scattering and reflecting objects. Some of the paths from interfering BSs via scattering objects to the user are shown with 319 red lines.

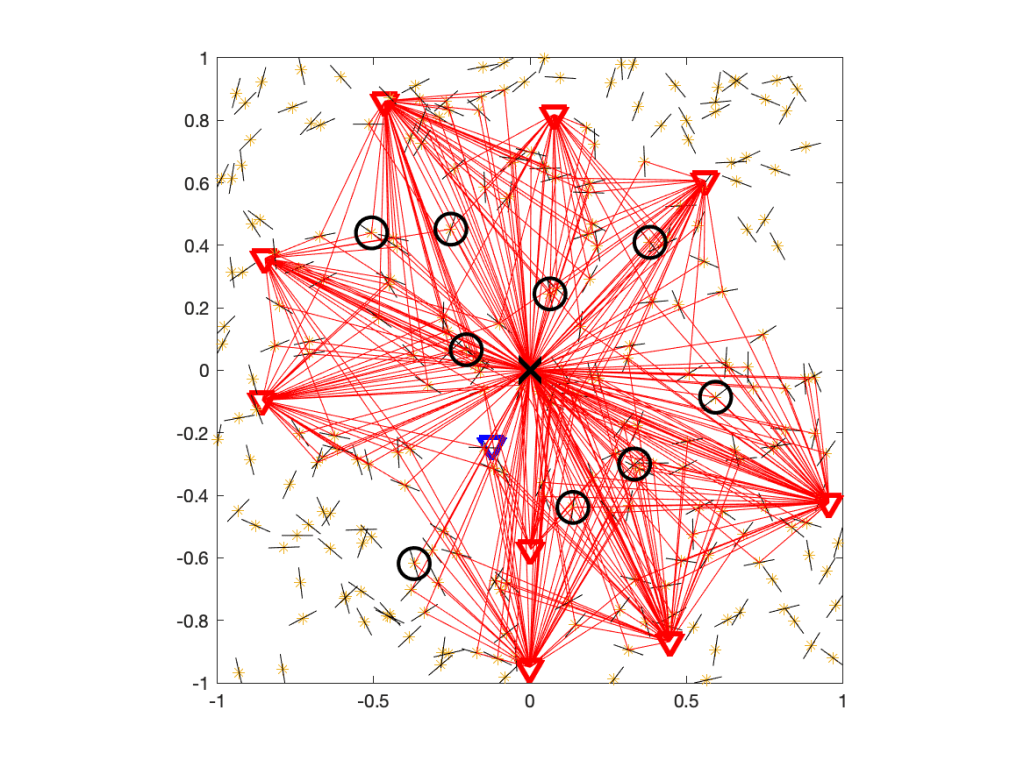

Now, let’s add one IRS per interfering BS. The resulting propagation environment is shown in Figure 2.

From the perspective of the user at the origin, the IRSs are unmatched, which means they act just like any of the other scattering and reflecting objects. So the difference to the IRS-free case is that there is a tiny fraction of additional scatterers, as highlighted in Figure 3.

In this case, the IRSs add 4% to the scattering objects. If we did raytracing, they could make a small difference. In analytical work where the fading model is based on the assumption of a large number of scatterers, with the number of propagation paths tending to infinity, they make no difference at all. So we conclude that there is no extra interference Q due to the presence of passive IRSs and thus I=IBS. The signals reflected at unmatched IRSs are no different from signals reflected at any other object, and multi-path fading models already incorporate all such reflections.

Another argument that IRSs cannot cause extra interference is based on the fundamental principle of energy conservation. If Q did exist, its mean would be proportional to the density of IRSs deployed. This implies that there would be a density of IRSs beyond which the “interference” from the IRSs exceeds the total power transmitted by all BSs, which obviously is not physically possible.